‘Punctual Urbanisms’ Framework Proposed by UArizona Researchers Clarifies Small-Scale Urban Planning Interventions

Punctual urbanism in Queens, New York.

Street Lab

Guerrilla urbanism. Lighter, quicker and cheaper. Insurgent urbanism. Pop-up urbanism. These are just some of the 16 terms used widely, though rarely evenly, for rapid planning responses to urban problems.

For University of Arizona PhD student Monica Landgrave-Serrano, Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning Philip Stoker and Assistant Professor of Public and Applied Humanities and Affiliated Assistant Professor of Architecture and Urban Planning Jonathan Jae-an Crisman, this wide variety of often overlapping terms is problematic, not only for scholars who study urban planning but also for practitioners who implement the interventions that by their very nature are executed quickly and inexpensively. Their solution: a new framework called “punctual urbanism.”

In a paper published in 2021 in the Journal of Planning Literature, Landgrave-Serrano, Stoker and Crisman compiled and analyzed the many terms used to describe these small-scale planning interventions.

Why the term punctual urbanism? According to researchers:

- They are punctual—they respond quickly to an urgent need that has in some way been identified through participatory means as traditional planning processes prove to be too slow and cumbersome.

- They puncture the urban landscape in very site- and time-specific ways: they are generally small in scale, ranging from tiny interventions to larger interventions that nevertheless are imagined as sites of exception rather than adhering to master-planned and organized forms of urbanism. In terms of their temporality, they are conceived of as time-limited interventions, whether they are event-based, a pop-up or temporary installation, or, at most, are conceived as some kind of incremental element that may or may not proliferate over time.

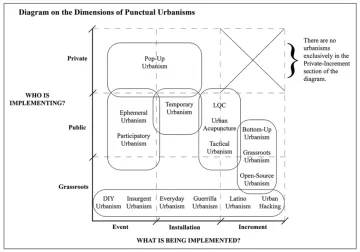

The framework further identifies the variance between different punctual urbanisms based on who is implementing the intervention—grassroots, public sector, private sector—and what is being implemented—event, installation, increment.

Diagram on the Dimensions of Punctual Urbanisms.

Philip Stoker

In their analysis, the researchers recognize that punctual urbanisms share common benefits and strengths, including serving as tangible civic engagement opportunities for citizens of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds, creating opportunities for inciting larger “movement[s] of city repair” and “bridging relationships between citizens and municipalities outside of traditional settings like public hearings and city meetings,” they say.

But punctual urbanisms also have shortcomings, most notably the “lack of an official public participation process that considers all stakeholders.” They may also have difficulty achieving long-lasting policy changes and can lead to gentrification.

Yet punctual urbanisms “have been demonstrated to be a useful approach in an increasingly complex and politically fraught urban context,” conclude the researchers.

With the overarching term of punctual urbanisms in place, additional analysis may be undertaken that helps define, for example, which interventions are more prominent, more successful and longer-lasting. Thanks to Landgrave-Serrano, Stoker and Crisman, these further explorations have a common framework from which to launch.